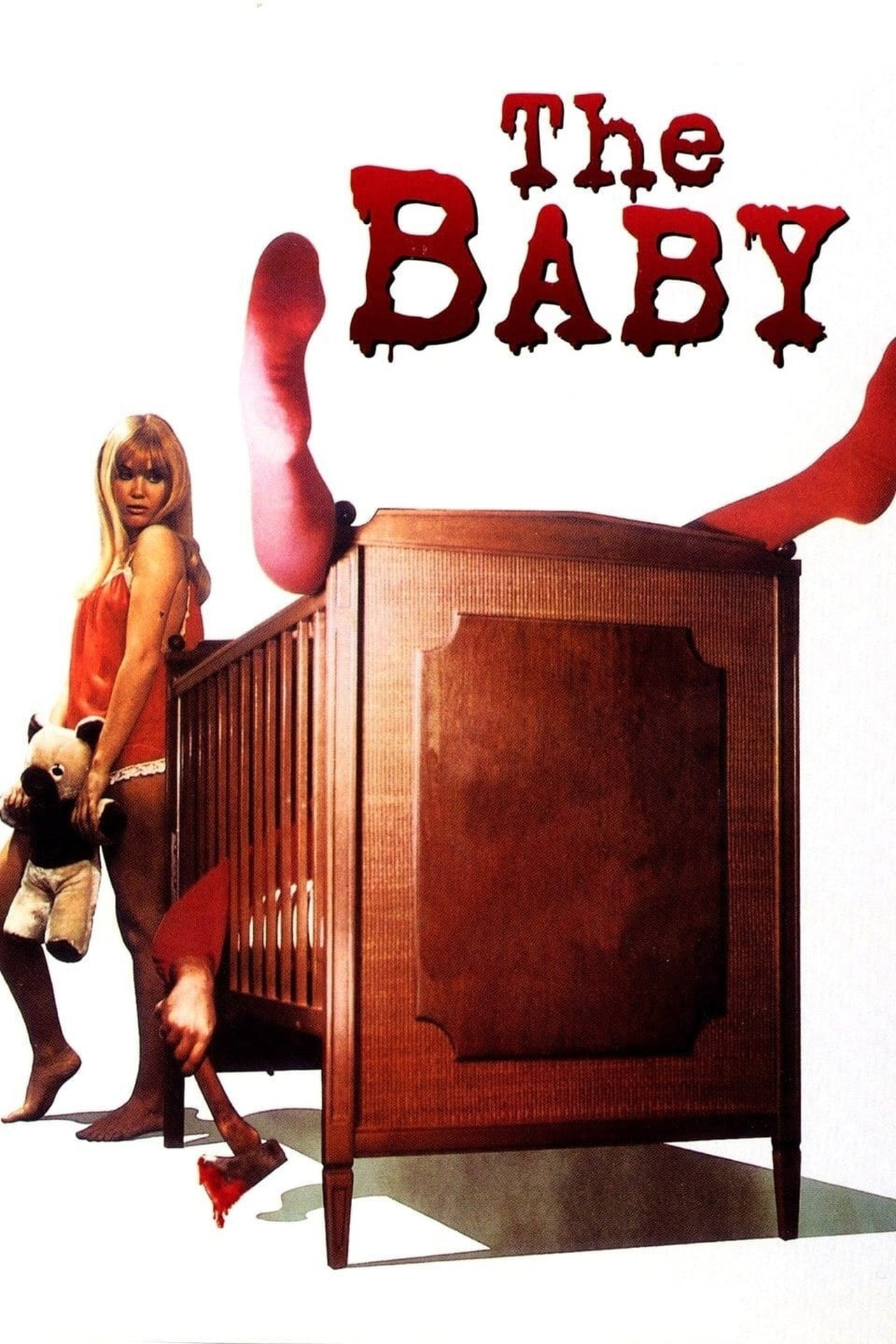

Social worker Ann (Anjanette Comer) visits the Wadsworth family to assess whether their welfare support for their child is legitimate. Upon arrival, she meets the so-called “baby”—a fully grown man named Baby (David Mooney), who has been raised and treated as an infant. While he is mentally challenged, that alone hardly justifies the use of a crib, pacifier, and diapers.

Ann soon realizes that Baby is far from being treated kindly by his family, which consists of an overbearing, ruthless mother (Ruth Roman) and his two beautiful yet unsettling sisters (Marianna Hill and Susanne Zenor). But rather than immediately intervening, Ann begins coddling Baby herself, as though he truly were an infant. As she digs deeper, it becomes clear that Baby is trapped in a sinister, abusive household, and Ann must do her best to free him from his family’s grasp.

This bizarre ’70s film stands apart from most of the movies banned by Norway’s Film Censorship Board at the time. Typically, films were censored for excessive sex, graphic violence, or both. The Baby, however, contains no nudity and only a handful of violent scenes that should have easily passed the censors. And yet, the film is deeply disturbing on multiple levels, making it easy to see why the moral gatekeepers of the era were alarmed by its content. A grown man in diapers being breastfed, incestuous undertones, and the torture of a mentally impaired character—these are elements bound to make audiences uncomfortable.

The Baby is a dark and unsettling film that lingers in the realm of cult cinema. It is not for mainstream audiences and remains an underground curiosity. Watching it today, the film feels very much a product of its time, lacking the timeless quality of many other ’70s classics. The pacing is sluggish, and both the directing and editing feel locked in their era. Additionally, the film never fully embraces its own bizarre premise the way something like Bad Boy Bubby does, a film that leans into its absurdity with a more self-aware, playful approach. The Baby also features a plot twist clearly designed for shock value, making for an entertaining but somewhat cheap conclusion. It works well enough as a final jolt, but those looking for more depth may find it unsatisfying.

Screenwriter Abe Polsky spent a year convincing director Ted Post to take on the project, as Post initially found the subject matter too dark. Watching The Baby today, it’s easy to understand his hesitation—it’s almost surprising that he eventually agreed. At the time, Post had a solid career, having directed Clint Eastwood’s western Hang ‘Em High (1968) and the Planet of the Apes sequel Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970). So in that sense, agreeing to direct a deeply bizarre film about an adult baby might not have been the wisest career move.

If you’re looking for something completely out of left field, a movie that will leave you wondering, “What the hell am I watching?”, then The Baby is worth checking out. It’s darkly humorous, unsettling, and absurd, packed with unexpected narrative turns. At the same time, it’s cheesy and leaves behind a lingering sense of unease. A bigger budget might have resulted in a more refined execution, yet The Baby still feels like the work of competent filmmakers who knew exactly what kind of oddity they were crafting.

Ultimately, The Baby is one of those films you have to see for yourself to fully understand why it has remained such an infamous piece of cult cinema.